Typing “Siberia Vladivostok” into a search bar often reflects a basic uncertainty Is Vladivostok really part of Siberia? Why does this far-eastern city matter so much? And what does it reveal about Russia beyond the familiar imagery of frozen taiga and labor camps? The answers lie at the intersection of geography, power and lived experience.

Siberia Vladivostok is not a contradiction—it is a culmination. Vladivostok sits at the eastern terminus of Siberia’s long historical arc, a city where the continental sweep of Eurasia finally meets the Pacific Ocean. Founded in 1860 and opened to the world only after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Vladivostok embodies Siberia’s paradoxes remote yet global, militarized yet cosmopolitan, strategically vital yet demographically fragile.

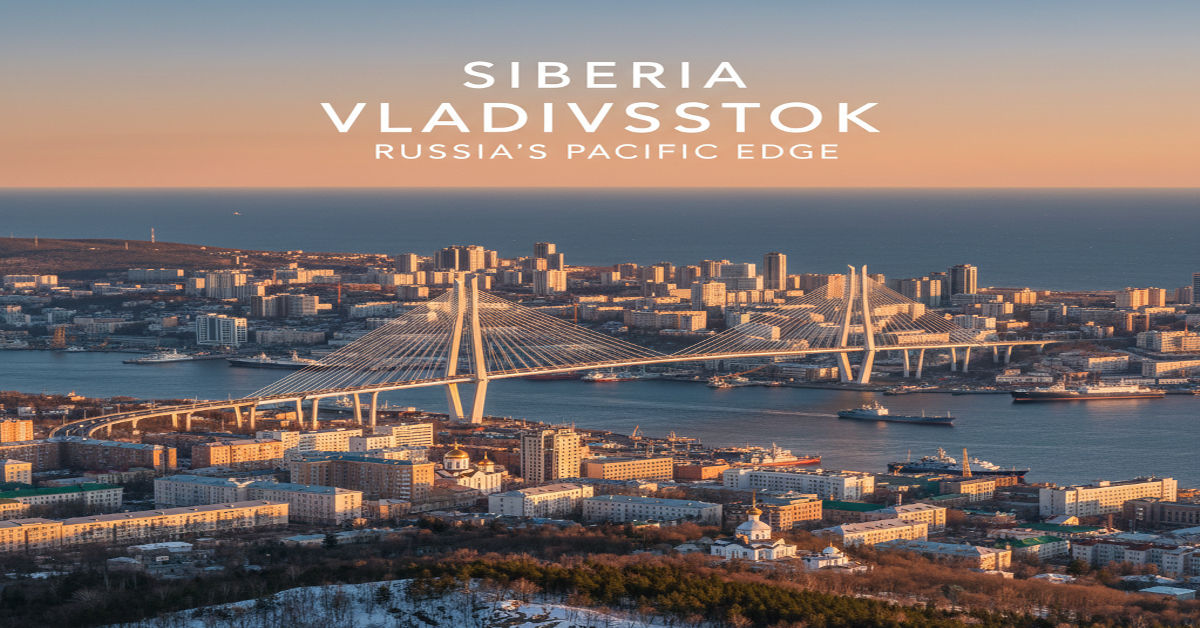

Within the first moments of understanding Siberia Vladivostok, one fact becomes unavoidable: this city matters far beyond its population size. It is Russia’s principal Pacific port, the headquarters of the Pacific Fleet and the symbolic end of the Trans-Siberian Railway. It is also a place where Korean grocery stores sit beside Soviet apartment blocks, where Japanese cars dominate the streets and where young Russians imagine futures oriented not toward Moscow, but toward Asia.

This long-form examination traces how Siberia Vladivostok came to occupy such an outsized role in Russia’s geography and imagination. It explores how history, climate, infrastructure, and geopolitics shape daily life at the edge of the continent—and why understanding Vladivostok is essential to understanding Siberia itself.

Where Siberia Vladivostok Fits on the Map

Administratively, Vladivostok belongs to the Russian Far East Federal District, not the Siberian Federal District. Yet historically, culturally and symbolically, Siberia Vladivostok has been bound together for more than a century. The eastward expansion of the Russian Empire treated Siberia as a single vast frontier, and Vladivostok emerged as its maritime endpoint.

Geographically, Vladivostok occupies the Muravyov-Amursky Peninsula, flanked by the Sea of Japan and a series of deep natural bays. It lies closer to Seoul and Tokyo than to Moscow, a fact that underscores its Pacific orientation. The distance from Moscow—9,288 kilometers by rail—is not just physical it is psychological.

The climate reinforces Vladivostok’s distinctiveness within Siberia. While interior Siberia is defined by extreme continental cold, Vladivostok experiences a monsoon-influenced climate. Winters are dry and windy, summers humid and fog-laden. This climatic hybridity mirrors the city’s cultural position between Siberia and East Asia.

As the geographer Mark Bassin has argued, Siberia was long imagined as “a space of future possibility rather than a marginal periphery” (Bassin, 1999). Siberia Vladivostok transformed that imagined future into a port, a fleet, and a geopolitical foothold on the Pacific.

Imperial Ambition and the Birth of Siberia Vladivostok

Vladivostok was founded in 1860 following the Treaty of Beijing, which transferred large territories from Qing China to the Russian Empire. The name—meaning “Ruler of the East”—was no accident. From its inception, Siberia Vladivostok was designed as an assertion of imperial presence at the edge of Asia.

In its early decades, the city grew as a military outpost and trading port. Chinese laborers, Korean farmers, Japanese merchants, and Russian settlers coexisted uneasily, creating a multiethnic frontier society. The completion of the Trans-Siberian Railway in 1916 cemented Vladivostok’s permanence, anchoring it to the Siberian interior.

The Russian Civil War briefly turned the city into an international battleground, occupied by Japanese, American, and other Allied forces. When Soviet power consolidated, Vladivostok’s role shifted decisively toward defense. By the mid-20th century, Siberia Vladivostok had become one of the most heavily militarized cities in the Soviet Union.

Historian David Wolff notes that Vladivostok’s development reflected a broader pattern: “The Russian Far East was integrated into the empire not through gradual settlement, but through strategic infrastructure and force” (Wolff, 1999). Nowhere was this more evident than in Vladivostok.

A Closed City at the Edge of Siberia

In 1958, Vladivostok was officially designated a closed city. Foreigners were barred, and Soviet citizens required special permits to enter. For more than three decades, Siberia Vladivostok existed in near-total isolation from the outside world.

This secrecy had profound consequences. While military shipyards and research institutes received funding, civilian infrastructure lagged. Consumer goods were scarce. Travel was restricted. Yet the city also developed a strong internal culture—self-reliant, skeptical of Moscow, and shaped by proximity to the sea.

Stephen Kotkin describes closed cities as “engines of Soviet modernity hidden behind walls of secrecy” (Kotkin, 2001). In Siberia Vladivostok, that secrecy fostered both technological expertise and social stagnation. Residents knew they lived somewhere important, but were cut off from the benefits of openness.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Vladivostok reopened almost overnight. The sudden exposure to global markets was destabilizing. Japanese used cars flooded the streets, Chinese traders filled markets, and informal economies flourished. For the first time in generations, Siberia Vladivostok could look outward.

The Trans-Siberian Railway and the Meaning of Arrival

The Trans-Siberian Railway is inseparable from the idea of Siberia Vladivostok. Stretching across eight time zones, it links European Russia to the Pacific, making Vladivostok not just a city, but a destination—the end of the line.

Construction began in 1891 and took a quarter century. It transformed Siberia from an imagined void into a connected space. Grain, timber, coal, and people flowed east; manufactured goods flowed west. Vladivostok became the hinge between land and sea.

For travelers, arriving in Vladivostok by train carries symbolic weight. The final station marks the completion of a continental journey. As Wolff observed, the railway “did more than move goods; it created a mental map of Russia as a Pacific power” (Wolff, 1999).

Despite aging infrastructure and competition from maritime routes, the railway remains central to Vladivostok’s identity. In the story of Siberia Vladivostok, steel tracks bind geography to imagination.

Siberia Vladivostok by the Numbers

| Indicator | Vladivostok | Interior Siberia (Average) |

| Population (2021) | ~603,000 | ~300,000 (urban centers) |

| January Avg. Temperature | −12°C | −18°C |

| Distance from Moscow | 9,288 km | 3,000–5,000 km |

| Economic Focus | Port, military, logistics | Mining, energy, metallurgy |

Sources: Rosstat; Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Port, Fleet and Pacific Strategy

Vladivostok’s port is the economic and strategic heart of Siberia Vladivostok. One of Russia’s few Pacific ports with year-round access, it anchors trade routes linking Siberian resources to Asian markets.

The city also hosts the headquarters of the Russian Pacific Fleet, underscoring its military significance. During the Cold War, this made Vladivostok a linchpin of Soviet naval strategy. Today, it remains central to Russia’s security posture in East Asia.

Since 2015, Vladivostok has hosted the Eastern Economic Forum, designed to attract investment into the Russian Far East. President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly framed the development of the region as a national priority, stating that Russia’s future growth depends on its eastern territories (Putin, 2013).

Yet results have been mixed. While infrastructure has improved, demographic decline persists. Siberia Vladivostok continues to lose population to western Russia, a reminder that strategic importance does not automatically translate into livability.

Siberia Vladivostok vs. Interior Siberia

| Dimension | Interior Siberia | Siberia Vladivostok |

| Orientation | Continental | Pacific |

| Historical Role | Exile, extraction | Naval gateway |

| Cultural Influences | Russian, Indigenous | Russian, East Asian |

| Economic Model | Resource-based | Trade-based |

Daily Life on Siberia’s Pacific Edge

Life in Siberia Vladivostok is shaped by contrasts. The city’s hills offer sweeping views of the sea, but infrastructure struggles with age and climate. Prices are high, wages uneven, and travel expensive. Yet residents often speak of a freedom absent in western Russia.

Sociologist Natalia Zubarevich has described the Russian Far East as living in “permanent tension between strategic attention and everyday neglect” (Zubarevich, 2018). Nowhere is that tension more visible than in Vladivostok.

Young people face a familiar Siberian dilemma: leave or stay. Increasingly, some look south rather than west, studying Korean or Chinese, imagining careers tied to Asia. In this way, Siberia Vladivostok is quietly redefining what it means to belong to Siberia in the 21st century.

Takeaways

- Siberia Vladivostok represents the Pacific culmination of Siberia’s eastward expansion.

- The city’s history as a closed military zone still shapes its infrastructure and culture.

- The Trans-Siberian Railway gives Vladivostok symbolic and economic meaning.

- Vladivostok’s climate and geography distinguish it from interior Siberia.

- The city is central to Russia’s Asia-Pacific strategy, with uneven outcomes.

- Daily life reflects a balance between global orientation and local challenges.

Conclusion

Siberia Vladivostok is not simply a geographic label it is a narrative about how nations imagine their edges. At the far end of Eurasia, Vladivostok compresses the story of Siberia into a single city—one shaped by empire, secrecy, resilience, and reinvention.

To stand on the Golden Horn Bay is to feel both the weight of distance and the pull of connection. The sea opens outward, even as the land stretches endlessly behind. This duality defines Siberia Vladivostok: a place born of continental ambition but sustained by oceanic horizons.

As global trade shifts, climates change, and geopolitical lines harden, Vladivostok’s role may evolve again. Whether it becomes a true Pacific metropolis or remains a strategic outpost depends on choices yet to be made. What is certain is that Siberia’s story does not end in forests and frost—it ends, unmistakably, at the water’s edge.

FAQs

Is Siberia Vladivostok an official term?

No, but it is commonly used to describe Vladivostok’s historical and cultural connection to Siberia.

Why is Vladivostok associated with Siberia?

Because it was founded through Siberia’s eastward expansion and connected via the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Is Vladivostok colder than Siberia?

Winters are cold but generally milder than interior Siberia due to maritime influence.

Why was Vladivostok closed during Soviet times?

Because of its strategic importance as a naval base and military-industrial center.

What makes Siberia Vladivostok unique today?

Its Pacific orientation, multicultural influences and role in Russia’s Asia-Pacific strategy.

References

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024). Vladivostok. https://www.britannica.com/place/Vladivostok

Rosstat. (2022). Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities. https://rosstat.gov.ru